What Babygirl (2024) and Charles Bukowski Have In Common

Earlier this month Halina Reijin’s latest film, 'Babygirl,' saw its UK theatrical release. It hit cinemas in the US and Canada on December 25th 2024 teasing the phrase, “This Christmas get exactly what you want,” in its posters:

The film tells the story of Romy Mathis, played by Nicole Kidman, the CEO of a tech company. When intern Samuel joins the company, played by Harris Dickinson, the pair soon begin a steamy love affair. Romy expresses concerns that their power imbalance might lead to Samuel getting hurt. He reckons his ability to “make one phone call” could cause her to lose everything she has, giving him the power in their dynamic.

Since its release the film has garnered some critical acclaim, receiving nominations for the Golden Globes and the Satellite Awards. It's also collected several polarising reviews from audience members. Between pop-culture icon Ziwe deciding “Time should be measured in before babygirl (B.B.) and after babygirl (A.B.)” to other viewers claiming that:

Whether you love it or you hate it, you’ve probably heard about it. The large age gap between 'Babygirl''s love interests has pushed it to the forefront of many viewer’s minds. I know I won’t be the only person unable to escape from the discourse on social media.

The film attempts to flip the ‘powerful older man,’ and ‘naive younger woman’ stereotype on its head. A stereotype which has been overplayed time and time again in films like ‘Lost In Translation’ (2003), ‘Fifty Shades of Grey’ (2015), and ‘Secretary’ (2002). Patrick Sproull identifies that ‘Babygirl’ is not the only film to subvert this trope in an article for The Face. Citing 2024’s ‘The Idea Of You’, starring Anne Hathaway and Nicholas Galitzine as its romantic leads, along with other examples.

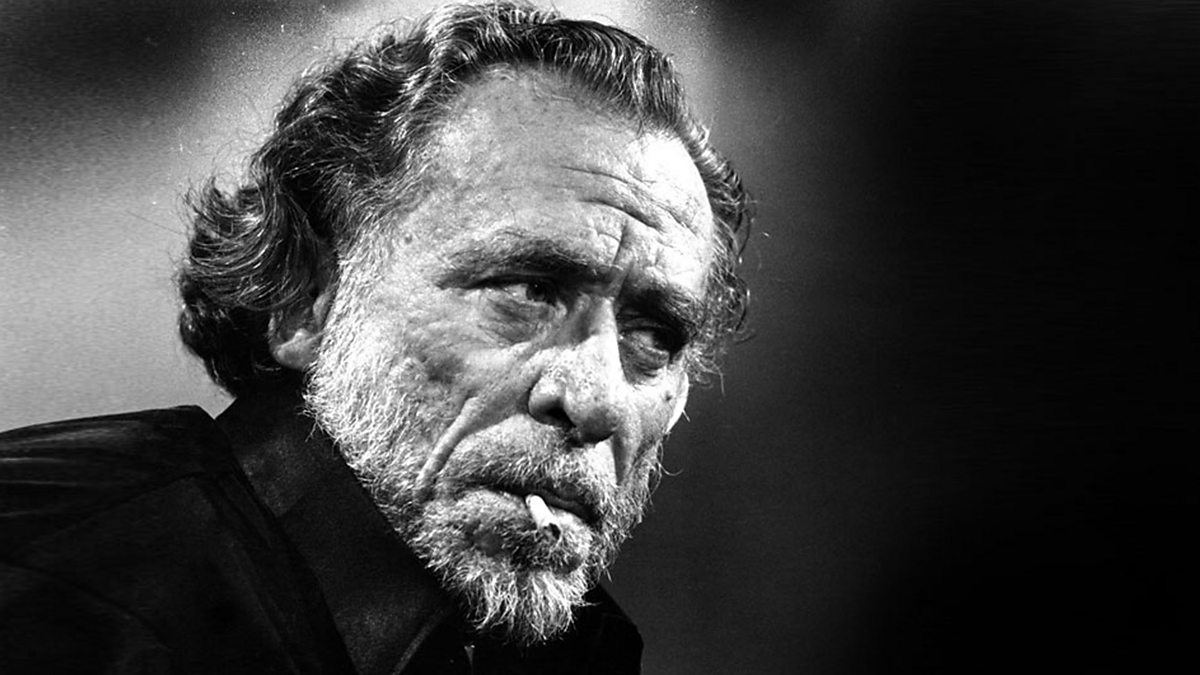

This influx of older woman/younger man romance films has drawn my mind towards a poem by American writer Charles Bukowski, ‘my first affair with that older woman.’

I first discovered this poem while reading my copy of ‘You Get So Alone At Times That It Just Makes Sense.’ This collection of Bukowski’s poems was first published in 1986. As its title suggests, 'my first affair with that older woman' tells the tale of a relationship the narrator had with an older woman, a relationship that did not have the happiest of endings:

‘when I look back now

at the abuse I took from

her

I feel shame that I was so

innocent,

but I must say

she did match me drink for

drink,

and I realised that her life

her feelings for things

had been ruined

along the way

and that I was no more than a

temporary

companion;

she was ten years older

and mortally hurt by the past

and the present;

she treated me badly:

desertion, other

men;

she brought me immense

pain,

continually;

she lied, stole;

there was desertion,

other men,

yet we had our moments; and

our little soap opera ended

with her in a coma

in the hospital,

and I sat at her bed

for hours

talking to her,

and then she opened her eyes

and saw me:

“I knew it would be you,”

she said.

then she closed her

eyes.

the next day she was

dead.

I drank alone

for two years

after that.'

Born in Germany in 1920, as Heinrich Karl Bukowski, Charles moved to the United States with his family in 1923. After living in Maryland for several years, they then moved to Los Angeles in 1930.

As an adult, he lived in New York and then Philadelphia, but ultimately returned to Los Angeles, where he lived for most of his life. He gave up writing for some time, and in the 1950s he began writing consistently again and published his first collection of poems ‘Flower, Fist and Bestial Wail,’ by October 1960. He continued writing and publishing various novels and poetry collections throughout the 1960s, 70s, 80s, and 90s until he died in 1994 at the age of 73.

Bukowski was not someone who led a quiet life; he stirred up controversy during and after his lifetime. A common criticism aimed at his work is that it is oftentimes perceived as sexist. He has a whole poem dedicated to a trip to a brothel titled ‘whorehouse.’ It features charming verses such as:

'and right at the exit was an

old whore sitting in a

chair.

she stuck out her leg

barring our

way: “come on, boys, I’ll make

it good for you and

cheap!”'

After which a friend of the narrator, called Jack, promptly vomits into his own hat. Don’t think that'll put our narrator off, however. . . He powers on through, into a private room with the prostitute and a security guard for her safety. Once the deed is done the narrator returns outside to his friend and proceeds to brag about his conquests to Jack in a very childish, braggadocious manner.

Depending on who you ask, some argue that Bukowski is satirising these sorts of machismo attitudes, but it is a matter of opinion. Regardless of his attitudes towards women, his work undeniably features many thoughtful, realistic portrayals of women (alongside these other poems that cross the line, into crass or insensitive territory).

Despite his expansive discography spanning over three decades, I always find myself returning to ‘my first affair with that older woman.’ It’s such a quiet, touching poem that continues to resonate with me, years after I made my initial discovery of it.

Bukowski favours free verse for his poems and ignores the need to capitalise each line, breaking up his verses into short, conversational lines. The cumulative effect of his signature style endeavours to deliver the emotions at the core of each poem.

In one poem, he details the story of a drunken writer, drooling over himself at a bar, entertaining those around him with his tales. Yet, the writer is clearly wasting away from the drink. In this poem, ‘final story,’ the bleakness of the words hit like a truck. Trigger warning for graphic suicidal depiction:

“the people

come into the

bar

night after night

for the same old

show

which he will one day

end

alone

blowing his brains to

the walls.

the price of creation

is never

too high.

the price of living

with other people

always

is.”

Bukowski highlights certain words through his succinct verse structure, making the shorter lines hit like a punch to the gut. You are unable to escape the harsh reality this writer has condemned himself to.

On the other hand, in ‘helping the old’ where the narrator relates a brief incident helping an older man struggling to pick up his glasses:

“as I handed him his cane.

he didn’t speak,

he just smiled at me.

then he turned

forward.

I stood behind him waiting

my turn.”

The pair don’t exchange many words. Nothing else needs to be said. Yet Bukowski crafts an immense warmth throughout the select few verses; a mutual understanding between the narrator, the man, and the reader, invited into this event through Bukowski’s skilful storytelling.

Sadly, ‘my first affair with that older woman,’ is one of Bukowski’s more sombre poems. It ends with the harrowing image of the narrator unable to shake his solitude, turning to alcohol to cope for two years after the titular older woman’s death.

Without spoiling too much, Samuel’s affair with an older woman in ‘Babygirl’ has not been blessed with good luck either. Although you probably could have guessed that from the trailers.

Things clearly aren't always smooth sailing for Romy and Samuel. . . Yet, I’m glad this recent release has returned my attention to one of America's most iconic poets; specifically one of his most agonising poems.