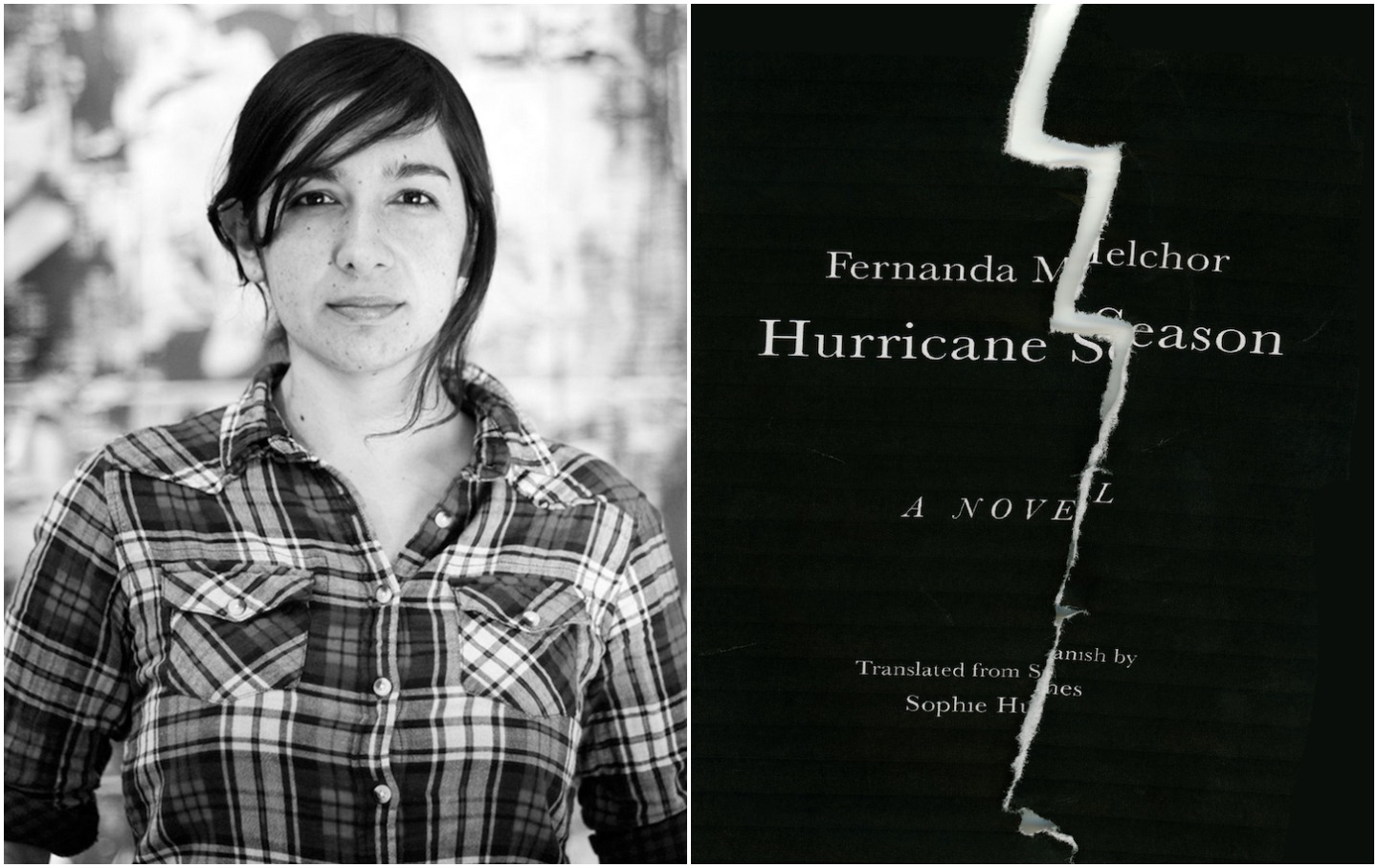

The Brutal Reality of Hurricane Season by Fernanda Melchor

‘Hurricane Season’ is author Fernanda Melchor’s first book published in English, translated by Sophie Hughes. The original Spanish edition of the novel ‘Temporada de Huracanes,’ was published in 2017, with the English edition released in 2020.

Before this, the novel was translated into German by Angelica Ammar, titled ‘Saison der Wirbelstürme.’ This version garnered notable critical appraisal, with Ammar’s translation winning the 2019 International Literature Award. Since then, Melchor’s novel has been shortlisted in 2020 for the International Booker Prize and the International Dublin Literary Award in 2021. The novel is her second publication, following a collection of short stories published in 2013: ‘Aquí no es Miami,’ translated by Sophie Hughes in 2023 as ‘This Is Not Miami,’ and ‘Falsa Liebre.’

Fernanda Melchor

‘Hurricane Season’ is concerned with life in a small, Mexican village, La Matosa, when a group of children find the local Witch dead in an irrigation canal. The novel unfolds across eight chapters; written in third-person, with each chapter exploring the perspective of a different central character. Chapter one is fairly short, setting the scene with a grizzly discovery of “the rotten face of a corpse floating among the rushes.” (Page 13, Fitzcarraldo Editions 2023)

This novel is not for the faint of heart, or the easily upset. Melchor spares us from none of the gruesome details relating to life in La Matosa and its surrounding towns. Scandalous activity ranges from drug use and graphic sex, to rape, bestiality, mutilation, and murder. Women and girls especially fall victim to the unfair yet unfortunately realistic circumstances that Mexican women are forced to experience. Melchor articulates the complex reality of life in Mexico in an interview for DW from 2019:

“There are lots of different environments in Mexico's society. So it's very diverse but it's true that there is a perverse situation of inequality that creates these really dark and really dangerous places and these particular crimes.

We all heard about the narco violence, the beheadings for example or the hanging of bodies from bridges. At the same time, Mexico is a place filled with really welcoming, warm and generous people, hard working people.

I just wanted to portray what can happen in a really small place, totally forgotten by the state and by society.”

Melchor relays her story through a non-chronological narrative, bringing us back in time in chapter two to explain the Witch’s history. We learn that she helps the women of the village with her witchcraft, dishing out various potions, some to attract men, some to wipe their memories, some to ward off unwanted attention but mainly potions to induce abortions.

The Witch chooses to help sex workers for free, and it is unclear whether this is due to her feelings of friendship for the women or a shared understanding between them of male violence. It is the sex workers who decide to raise a collection, intending to give the Witch a proper burial; a request that is denied by police, due to the ongoing investigation surrounding her death, and the lack of familial connection to the Witch. Within this chapter Melchor introduces her readers to one of the central themes of the text: the reality of violence. She crafts a model of sistership between the Witch and her clients from which empathy and genuine care emerge. Yet Melchor repeatedly demonstrates how this model of sisterhood is still subjected to the violence of a patriarchal society. As sex workers with male clientele, these women turned to the Witch for help after their unsavoury encounters with men. However, these women are unable to help the Witch in return after her murder due to the refusal of the powerful men occupying the police force.

After this point, this article ventures into spoiler territory so proceed with caution.

Chapter three brings us to Yesenia, a local girl striving to please her grandmother, yet always failing to emerge from her deadbeat cousin’s shadow. As her chapter unfurls we learn that this deadbeat cousin of hers, called Maurilio but referred to as Luismi, spends many of his evenings at parties in the Witch’s basement.

Chapter four introduces us to Munra, the driver of this car. Munra claims he doesn’t know anything, he didn’t see anything at all relating to the Witch’s death. He claims he thought it was all just a friendly quarrel. It is within Munra’s chapter that we learn of the Witch’s identity as a trans woman and her relationship with Luismi. Munra is in a relationship with Luismi’s mother, sharing residence on the same plot of land as his step-son. And so Munra bears witness to Luismi beginning a relationship with a pregnant 13-year-old runaway, Norma.

The dynamic between Yesenia and her grandmother cements the influence of the patriarchy on interpersonal relationships. Yesenia tirelessly works to please her grandmother. Her main desire is to successfully fulfil the roles her grandmother has tasked her with but always falls short. She is demonised by her grandmother and has the burden of her several cousins’ misbehaviour thrust upon her. Simply due to her position as the eldest grandchild. Despite Luismi’s debauchery he never feels the wrath of his grandmother. Their family acts as a microcosm of the unfair expectations Mexican society often places upon its women, and the unbalanced consequences women face when they defy these expectations as opposed to men. One morning, before the discovery of the Witch’s body, Yesenia takes particular interest in a car parked outside the Witch’s home.

Chapter four introduces us to Munra, the driver of this car. It is within Munra’s chapter that we learn of the Witch’s identity as a trans woman and her relationship with Luismi. Munra’s chapter explores the realities of transphobia within our contemporary world. He hates the Witch and claims to feel uncomfortable in her presence, simply due to her existence. Thus, the context of the Witch’s transgender identity adds another element of tragedy to her murder, relating this crime to the very real and prevalent issue of transfemicide. The term ‘transfemicide’ was coined by Latin American activists to describe the disproportionate violence experienced by transwomen. Thankfully action is being taken to attempt to resolve this horrific issue, as in 2024 a prison sentence of 70 years was introduced in Mexico City for the crime of transfemicide.

Munra is in a relationship with Luismi’s mother, sharing residence on the same plot of land as his step-son. Therefore, Munra bears witness to Luismi beginning a relationship with a pregnant 13-year-old runaway, Norma.

Trigger warning for sexual assault and rape in this next section.

Rather than tell her mother, for fear of her disbelief or refusal to help, Norma decides to run away intent on taking her own life. Once again the unfair consequences of life are displayed as Norma navigates her pregnancy, believing she has engaged in a consensual relationship, and thus will be punished as a result. We hear of no consequences for Pepe despite his crimes against a child. The lack of justice and options for victims like Norma is an issue Melchor verbalised in her interview with DW, explaining how

“In Mexico teenage pregnancy is just so normal; Mexico has the highest rate of the world. We don't have a right to abortion in Mexico. You can only do it in Mexico City, and it's not free, you have to pay. So I think the conditions people and especially women have to live in in Mexico are just horrible.”

When Norma’s money runs out she runs into Luismi who offers her a place to stay. Norma turns to the Witch for assistance in terminating her pregnancy, and she receives a potion. The Witch’s potion does induce an abortion but Norma’s bleeding will not stop, forcing her to hospital, where she is detained by social workers. The system intended to protect victims like Norma in actuality work against her, resulting in her incarceration in hospital.

Chapter six is centred around Brando, one of Luismi’s friends. Brando is consumed by thoughts of self-doubt and perversion. His paragraph is almost on par with Norma’s for disturbing content. Brando is constantly concerned with protecting his public image and maintaining a persona of potent masculinity in front of his friends. He also develops an addiction to pornography as a teenager and attempts to suppress his desire for his best friend, Luismi.

Years of suppressing his feelings, his over-consumption of pornography and his continual anxiety surrounding his own masculinity culminate in Brando experiencing persistent thoughts of violence. He pesters Luismi with plans of stealing the rumoured gold concealed in the Witch’s house. The robbery goes awry and the Witch is brutally beaten by the pair and then stabbed several times. Brando slits her throat and the Witch's body is dumped in an irrigation canal.

Brando’s perspective is the most violent of all the chapters as Melchor overwhelms her readers with his consistent urges to hurt anyone that he believes threatens his masculinity. Through his discovery of and subsequent addiction to pornography, Melchor aligns the male violence entrenched in Brando with the objectification of women within these films. It is inferred that an upbringing filled with pornographic images has mangled Brando’s perspective on women and contributed to his disproportionate violent reactions. The destructive power of a patriarchal society is displayed as a negative influence upon both male and female characters - nobody can escape these cultural expectations. No matter how they choose to fulfil or avoid these expectations, they still dictate their actions as either aligning with or defying said expectations.

The final two chapters, like the first, are significantly shorter in length than the rest. The penultimate chapter explains how the Witch’s murder has set the women of the village on edge. But, this is a tension felt by women all over Mexico as the third-person narrator lists a series of other violent crimes in the region, mainly committed against women:

“Like that twelve-year-old kid who killed his girlfriend in a jealous rage on discovering that she was pregnant with his father’s baby,[...] Or that other miserable bitch who suffocated her little girl, jealous of all the attention the husband gave her,[...] Or those bastards from Matadepita who raped and killed four waitresses and whom the judge let off.” (Page 213-214)

This book is enthralling, spinning the plot in a new direction with each new character. The chapters feature no paragraph breaks, which can make it daunting at first to open a page and be met with a huge block of text. However, once you’ve read the first page you will not want to put it down. Melchor’s writing mirrors the delivery of a conversation - a long debrief from a close friend about the latest news. If strong language does not sit well with you then I would heavily suggest avoiding this one, as most of the sentences are dotted with expletives.

If that doesn't bother you, then I would thoroughly recommend this novel. However, you should prepare yourself for the contents, as it does not leave much up to the imagination, including its uncomfortable aspects. Or, if you do find any of these topics triggering, I would suggest avoiding this one altogether.

For those who can steel themselves, Melchor’s novel is worth the read. In an article about the prevalent rates of violence against women in Mexico, Mie Hoejris Dahl highlights how “over seven in 10 women and girls aged 15 and older report having experienced some form of violence, according to INEGI, the national statistics agency.” Melchor weaves the concerning treatment of Mexican women into her novel and handles the subject with the respect and care it deserves. She fleshes out each of her characters, elicits empathy for the plight of these women and calls attention to the discrimination they experience which their society encourages. But her interest is not limited to the plight of women. The negative ramifications of gender expectations are felt by the male characters as well as they strive for an impossible, intangible goal of perfect masculinity. ‘Hurricane Season’ is a shocking and upsetting but immensely important book.